Prototypes, production & fidelity layers

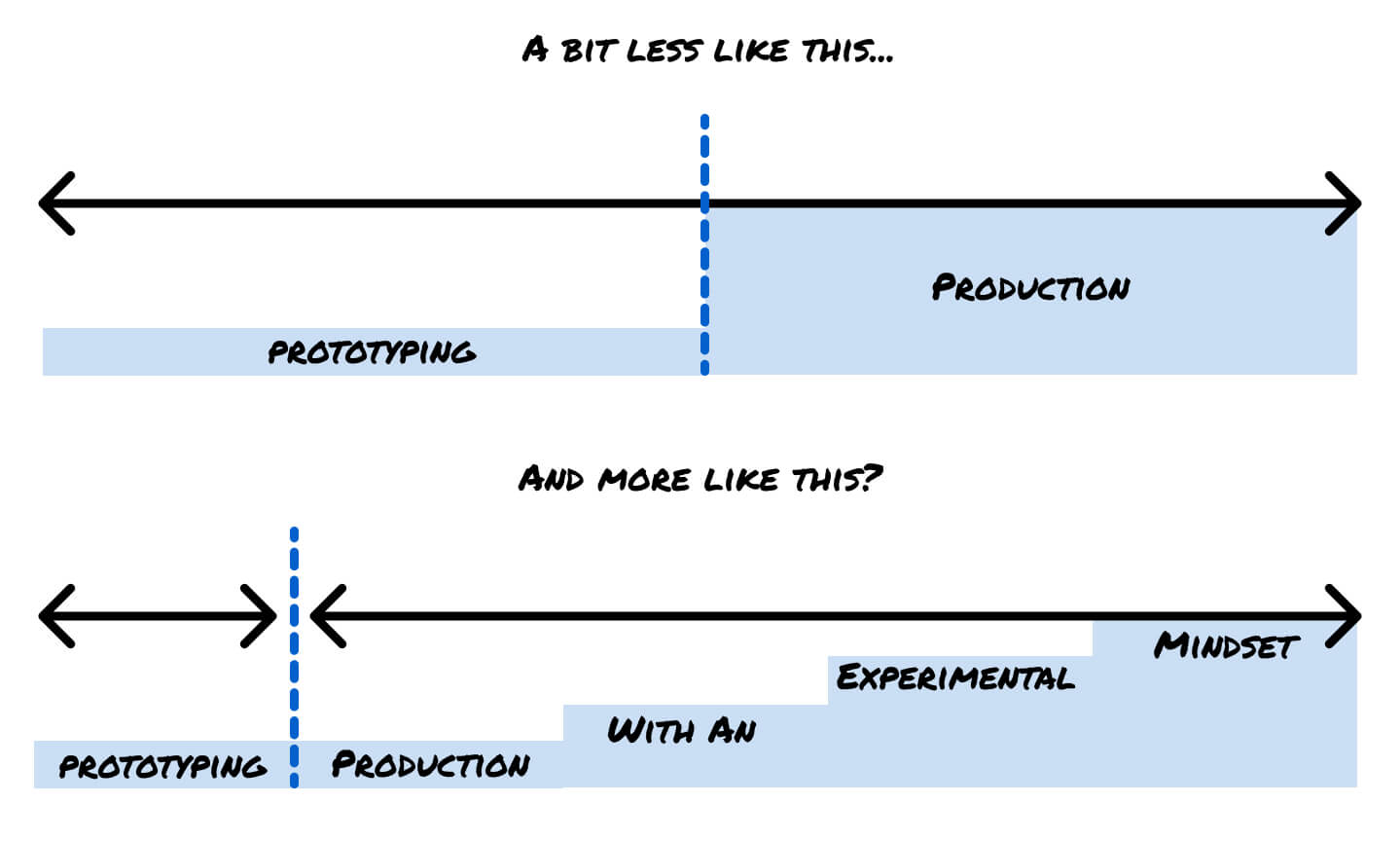

Posted on in WebThe mindsets for writing production and prototype code are often portrayed as binaries. Production code should be solid, serious and battle-hardened, whereas the fleeting nature of prototypes means they’re approached with a ‘good enough’ mindset.

But if I learned anything from working at a startup that ran out of runway, it was that so much of our production code is ultimately fleeting. It doesn’t matter how many hundreds of thousands of lines were committed in good faith by great engineers, decisions outside our control usually dictate their lifespan.

There’s still undoubtable a place for throwaway prototypes, but that doesn’t mean production code can’t learn a thing or two from the prototype mindset.

Identify your pace layer

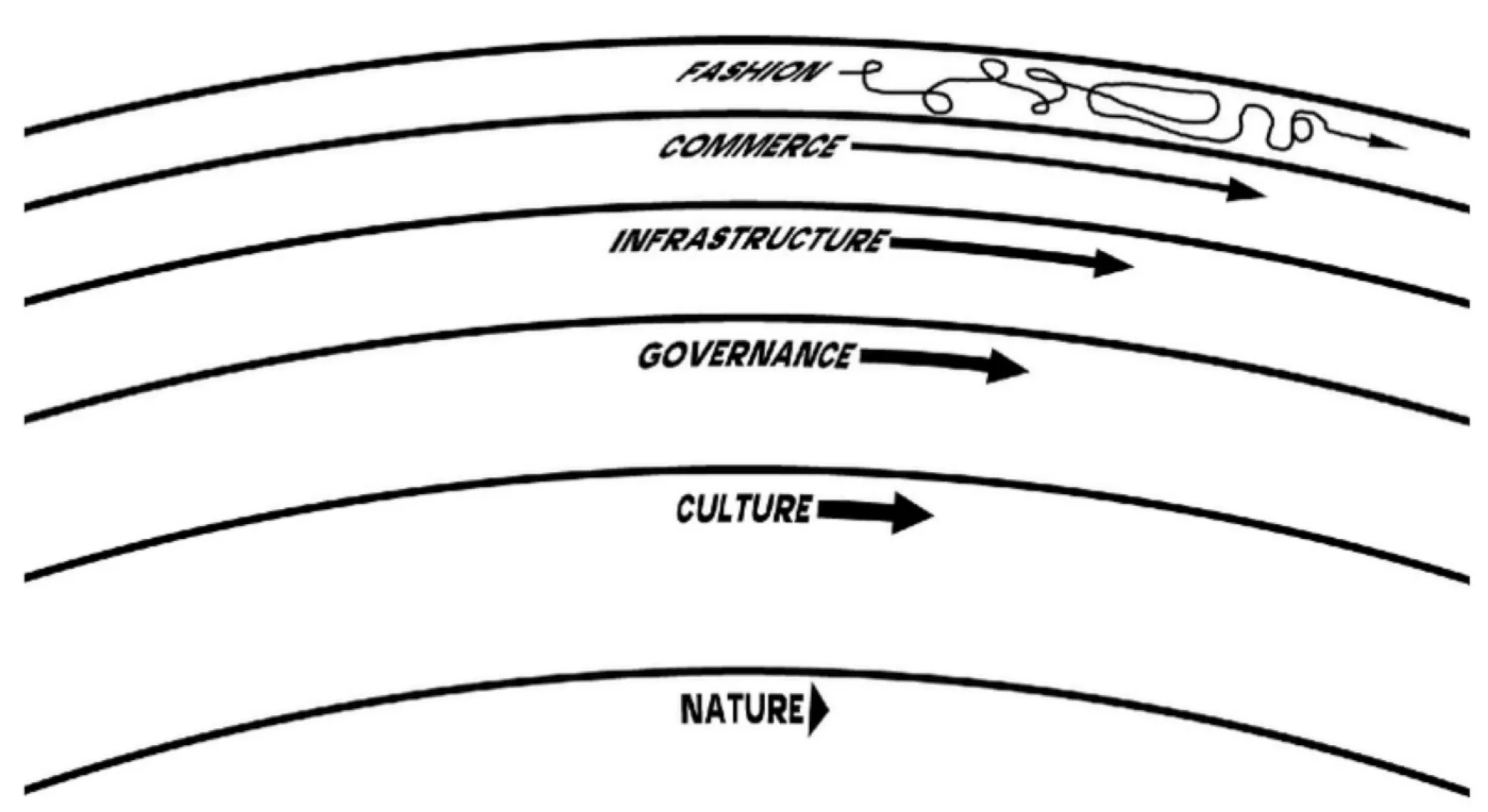

Stewart Brand’s pace layers, despite becoming design thinking cliché, continues to be a useful expression of organisational structure.

The concept maps a healthy civilization, where components operate independently with different change-rates, scales and speeds. The inner layers are slow, powerful and not easily shaken. The outer layers are quick, adaptable and attention grabbing.

At a meta-organisational level, this explains why startups can move nimbly but exist precariously. Well-established companies take time to react, but can weather many storms. Within an organisation, you’ll be able to think of factions, departments and components and place them on different pace layers. Identifying which layer your project exists in is a useful test for deciding the fidelity required.

Code for projects sitting within an inner ring demands more time and care. It will likely exist for longer, influencing the layers around it, making it harder to unpick. Conversely, projects sitting further out are inherently more experimental and less ‘risky’ to the business.

We don’t build ‘a web application’, we build hundreds of features, services & components that unite to form an application. Each of these chunks exists along this spectrum, and don’t have to be placed in the production camp. Not from day one. We can play with the form.

Slice up your fidelity layers

Taking a prototypical mindset, consider how you can slice a feature into distinct deliverable layers. The most basic layer; the MVP if you will, should always be accessible, acceptably performant and robust enough to live in production for some amount of time. But beyond that, challenge assumptions on how this feature would traditionally be built. What if you used a native HTML element, rather than a bespoke component? What if you manually uploaded that data, rather than building a comprehensive API and database. What if the image carousel was a single static image to begin with?

Each slice should consider the pro’s and con’s of launching at this level, as well as an understanding of what we can still learn from this lower effort & output iteration. Keeping the production north star in mind, we can avoid painting ourselves into a corner, while still providing value to the user early.

If every slice adds value to either the user, the developer experience or the business bottom line, selling this approach to stakeholders is considerably easier. It avoids the scenario where a ‘good enough’ prototype lives in production because there’s no appetite to fix it.

Each slice becomes a contained experiment, a bet at what we think will resonate with our users. These experiments celebrate success & failure equally; both are opportunities to learn. A psychologically safe space like this fosters innovation and gives agency to try new approaches.

If the experiment goes right? ✨ Great! We can move to the next layer and/or throw more money/people/resources at the problem. If the feature flops? ✨ Great! Thanks to the outer ring thinking, we’ve optimised for deletability by not tightly coupling this experiment to inner ring services.

This might sound like a lot of effort, but I promise this is a muscle that simply needs training, particularly if you’ve only ever worked in a ‘production’ mindset.

Lower fidelity does not mean cutting corners

It would be easy to jump to the conclusion that fidelity === quality, and that I’m advocating we ship services of lower quality. But I don’t think it’s that clear cut. Quality can be measured in all manner of ways.

Maintainability, manageability, testability, design accuracy, data timeliness, interoperability, measurability, adaptability. The priorities of these non-functional requirements (spot the -ilities) for your feature can be changed. A slice could sacrifice data timeliness to prioritise adaptability or time to market.

It requires real intentionality to pick the right approach, the vision to ensure you’re not painting yourself into a corner, and the confidence to take a calculated risk.

Walking the walk

I recently shipped a feature that has ‘untimely data’; data that’s a few hours, or up to a day old.

- Is it ideal? Of course not.

- Will the user notice? Probably not at this stage.

- Was it months quicker to ship? Without a doubt.

- Has it already unearthed a tonne of assumptions in our product. Absolutely.

Spending months on getting timely data would have simply delayed the discovery of these problems. We can fix these before we would have even launched the ‘perfect’ solution. The key was identifying that this non-functional requirement wasn’t actually as important as getting people onto the product.

In another example, I was building a component for an upper ring product, and this component was on the backlog for the design system team. Perfect, a great opportunity to kill two birds with one stone, right? Well, no - I made the decision not to add a component to the design system immediately. Good design systems live in a lower pace layer than the projects they serve. They take time to consider many use-cases before adopting a pattern, testing new components thoroughly when they’re coded.

Adding this component to the design system is the end-goal, but it didn’t need to hold up shipping the component to the lower-risk product. As a parallel task, I created a pull request to the design system where I was able to not only hit test coverage thresholds, but provide a live example of how this component would be used ‘in production’.

Posted on in Web